For a little while now, I have been wondering whether I should make a disclaimer for those I enter into romantic relationships with, warning them of the possibility of them ending up in my work.

Unwittingly becoming a muse may be an occupational hazard for those who choose to date artists, especially those whose concerns are “human scale and are based on the specific, particular fixations and everyday details of our lives”. On a weekend visit to London, I pass some time before meeting my current beau by visiting Sophie Calle’s exhibition Take Care of Yourself at the Whitechapel gallery.

I received an email telling me it was over.

I didn’t know how to respond.

It was almost as if it hadn’t been meant for me.

It ended with the words, “Take care of yourself.”

And so I did.

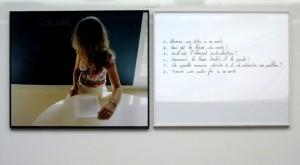

I asked 107 women (including two made from wood and one with feathers),

chosen for their profession or skills, to interpret this letter.

To analyze it, comment on it, dance it, sing it.

Dissect it. Exhaust it. Understand it for me.

Answer for me.

It was a way of taking the time to break up.

A way of taking care of myself.

The premise of the show is as follows. Calle has been dumped by a lover via email. She enlists over a hundred women from different professions in the production of 107 separate responses to the same initial text – ranging from framed texts and photographs, to videos, books, numerous translations of the text (into profit and loss accounts, legal documents and children’s stories amongst other things) and copies of the text used as target practice for archery or parrot food. The exhibition itself is quite overwhelming, and the collection of responses we are presented with is not easy to take in in one glance. It would be hard to ignore that the ‘activity’ undertaken here is intended to be both exhaustive and exhausting – just as repetitive, obsessive, bewildering, relentless and all-encompassing as being in love or feelings of loss can be.

Through this “summon[ing] of a whole squadron of women” (as writer Christine Angot puts it in her response to being given the email), Calle chooses a seemingly inefficient yet charmingly flawed or bittersweet way of attending to the situation see finds herself in. However, her investment in, and close examination of, this email draws our attention (as viewers) to this situation, not only engaging us in her personal experience of being dumped, but also coercing us into examining our own break ups and all of our previous (and future) positions or roles as ‘dumpers’ or ‘dumpees’.

The event itself is blown out of all proportion. What was initially a small, private and personal emergency, is now played out with the help of 107 uninvolved individuals, increasing its scale and impact for those previously ‘outside’ of this relationship through multiple translations (literal and figurative), “readings”, analyses, interpretations, responses, re-imaginings and commentary. When you enter the space of the exhibition, it would be hard to ignore the time, energy and effort spent in the simultaneous ‘processing’ and ‘making’ that has gone on to produce this work.

There is something I really respond to in this shifting of scale and that through simply paying this email far more attention than it probably deserves, it becomes un-ignorable – a very public echoing of the familiar private action of reading and re-reading the email/text message sent by a lover in the hope of deciphering or decoding it further, or in the hope of somehow ‘imbibing’ or absorbing it more fully, to the point where it becomes somewhat of an obsession.

In Take Care Of Yourself, our focus is directed towards a fragment of evidence and possible chain of events. The ‘facts’ of the situation are presented with a cool detachment (in a very ‘matter-of-fact’ way) and the possible ‘effects’ of the email (the potential for heart-break, feelings of shock, loss, surprise, loneliness, anger, fear or sadness, the unexpected necessity for new beginnings, moving on) are hammered home, if not only through sheer relentless repetition of the ‘facts’. This deadpan delivery, and simultaneous fictionalising of events, allows us to resist viewing this show as a simple affected emotional display. Instead, it seems to be indicative of a wry sense of humour – an outwardly effortless way of keeping us on our toes or not allowing us to become too complacent, where we can never be completely sure when the artist’s actions are a little tongue-in-cheek or deadly serious.

This strategy, of purposefully confusing (and complicating) fact and fiction to create an uneasy reportage of personal events, is familiar territory for Calle. Calle’s works (such as The Hotel and Double Game) are often task-led and rely on an interplay between Calle’s simultaneous statuses as an artist/author and her everyday existence as a ‘normal person’. Her works are framed by pretexts (the numerous ploys, ruses, red herrings and alleged reasons for her actions) that allow for, or specifically construct a space for, the subtext of the work. Their preoccupation with narrative (in the methods of both their construction and their presentation and in terms of form and content) mean that they lend themselves to becoming ‘shared texts’ – stories that are told and re-told by others who encounter the work. Forced Entertainment maybe most successfully exemplify this when they adopted Calle’s strategy of doggedly repeating the narrative of a break-up (employed in the piece/series Exquisite Pain), using the entirety of her repeated accounts of this as a ‘found text’ in their performance of the same name. For those who endured this two and a half hour performance, hearing the line “Six days ago, the man I love left me” being read over and over again as the preface to Calle’s changing explanation of events, is bound to hold a particular resonance – I certainly felt almost as though this had in some way become my own story simply by hearing it so many times.

We are reminded that, in each of our cases, these situations (of break-up/break-down), the remembering of them, and the ways in which we are called to deal with (and address) them publicly, through the necessity of informing, explaining and re-telling the news of the ending of relationships to our families, friends and acquaintances, become fictionalised – our understanding of “what went on” is, at best, provisional (subject to agreement and change), rather than the authoritative version it pertains to be. Take Care Of Yourself and Exquisite Pain both display an intense attention paid to a ‘text’ that becomes charged through a public re-playing – we are presented with repeated attempts to make sense of, to reconcile and to repair (oneself, not the relationship, which is referred to by the “quitter” as “irreparable”, as philologist Barbra Cassin in Take Care Of Yourself points out).

The way in which Calle enlists others to ‘play out’ the scenario and the offering of her ex-lover’s email as a ‘found text’ means that her work avoids becoming a simply cathartic exercise, moving it away from the domain of the personal towards something more universal and more recognisable. Its step into fiction encourages us to consider ourselves in the roles of the story’s protagonists.

Later in the weekend, I go to see Gob Squad’s film installation Live Long and Prosper at the Chelsea Theatre, which presents footage of performers from the company ‘playing out’ another set of ‘found texts’ in public. This time the ‘found texts’ are seven sequences from films like Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (the one where Spock sacrifices himself to save the ship and its crew), The Thin Red Line (an American WWII film made in the late 1990s) or Winnetou (a German western with Lone Ranger/Tonto-esque characters). We watch as the members of Gob Squad make their way, two-by-two, to their selected locations in various public spaces in Berlin – including a launderette, a pound-shop, a public space with some decking and a palm tree, a furniture shop and a shopping centre concourse. With care and attention to their costume and camera angles, they set about re-creating/re-playing their chosen scenes.

Two men get changed into the white polo-necks and red hoodies that become their Star Trek uniforms. They make last minute checks that eachother’s hair is not sticking up in the wrong places and position themselves either side of a shop’s closed plate glass doorway. Live Long and Prosper draws on an aesthetic we have become increasingly familiar with in an age of cheap consumer video technology and easy-to-publish-and-distribute YouTube videos – the fan film. Traditionally the domain of the amateur, fan films imply a particular type of attending to ‘found texts’ – a way of taking ownership over the thing you love, admire, or obsessed by through repeated watching, careful notetaking and storyboarding, (sometimes huge) personal investment and hours spent creating low-budget homemade costumes and sets.

As the narratives continue, we realize that each of the chosen scenes involves the death of one of its protagonists.

Gob Squad’s film asks us (as viewers) not only to re-consider the original film sequences, to watch intently as these new death scenes are played out to their inevitable conclusions alongside the originals, but also to pay closer attention to their content. We watch as Gob Squad ‘play out’ these scenarios as a dry run for the inevitable conclusion of all of our relationships. They practice saying goodbye, switching off the life support machine, taking one for the team, being the one who has to make the tough decision or the one who is left behind. This dress rehearsal might allow for mistakes to be worked through or ironed out, where there is less at stake if things go wrong or if the ‘players’ fluff their lines than in ‘real life’.

The ‘found texts’ (the film scenarios) may at first glance seem overused, overfamiliar or outmoded but Gob Squad’s sheer investment of time and energy in re-creating, shot for shot and line for line, these seemingly worn-out or clichéd images in public makes them far harder to dismiss or ignore. They treat these scenes (these ‘texts’) with the same kind of tenderness that the characters in the original films show for each other. Their homage not only demonstrates their affection for the source material, but the concentrated effort involved in remaking these scenes from scratch, in some way, shifts their status from simple Hollywood film narratives to significant cultural texts. As viewers, our understanding of the making process behind this work draws our attention back to academic ideas of undertaking a close reading – we realize that the performers must have spent a good deal of time ‘with’ and ‘concentrating on’ these scenes – watching, rewinding, fastforwarding and re-playing them.

The simulations-of-simulations presented here also ask us to re-examine what WE have been watching, not just here and now, but every time we have watched a film (or read a book, watched a play etc). Is it possible to suggest that each fictional portrayal of loss I watch/read could be a dry run for the death of a loved one or my own death, grieving, losing or being lost? And similarly, that I might not actually be able to encounter these emotions/situations in ‘real life’ without referring to the versions we have seen played out on films or TV? Maybe Gob Squad are suggesting that these scenes could provide prototype scripts for our own encounters with death?

I’m not sure, but the hurriedly fashioned costumes, borrowed film sets and hand-held ‘shoddiness’ of their interpretations remind me that these questions are being asked in a gently ironic or playful way. As in Calle’s work, this idiosyncratic shifting and tension between deadpan/detachment/straightness and playful/mischievous/humour and both artists’ impulsive and exaggerated ‘attending to’ gives us (as viewers) a time and space to consider something relatively serious – that unexpected (but inevitable) endings are not only part of our cultural language but also need to be part of a vocabulary that we are, or will be, called on to use in our own lives.

Like Take Care Of Yourself, Live Long And Prosper focuses on the making public of intimate moments. Like Calle, Gob Squad are fictionalizing fact, playing out fictions in the ‘real world’ and enlisting (or implicating) others (by appropriating public spaces and the invisible lives/people who inhabit them) in their process of making a response to something they have encountered in the world that seems unfathomable. Throughout Live Long And Prosper, the low production values, the lack of glamour and the recognizably mundane ‘sets’ used by the artists remind us that we (the viewers) could easily be the ones enacting these scenes.

As Gob Squad’s scenes end and their cameras pull backwards, retreating from their subjects, the surviving protagonists exit the shot and the “dead” are left where they fall. Just as quickly as the members of the company shifted from their ‘normal’ selves into their roles as cinematic stand-ins at the beginning of the piece, at its conclusion, we are reminded that all of this has been played out ‘in public’ – our attention is drawn back to the off-screen space and the world that has existed beyond the frame all this time.

The credits roll and the lights fade up. Once more it is time to put my coat back on and venture back out into the world…

[originally posted at http://thingsthatdontquitefit.wordpress.com in June 2010]

1 Comment

[…] This post has now migrated to http://rachel.we-are-low-profile.com/never-can-say-goodbye/ […]